Meet Mark

Mark is a 22-year-old college student at a Minneapolis community college who works as a delivery driver for a local pizzeria.

Mark is a 22-year-old college student at a Minneapolis community college who works as a delivery driver for a local pizzeria.

Mark's childhood was troubled and lacked parental guidance. He never knew his father, and his mother committed suicide when he was 14 years old. These factors took an emotional toll, and he started drinking alcohol when he was just 16 and then began using and selling drugs a year later. After learning he had contracted HCV, he was treated and cured a year ago, but is at risk of reinfection as he continues to use drugs. He was recently evicted from his apartment near campus due to chronically late rent payments over the past six months. Mark battles social anxiety and depression, and is currently failing many of his classes.

Mark recently started injecting drugs with some people he met near the local homeless shelter. With the loss of his home and an increasing dependence on drugs, he feels like his life is slipping out of control.

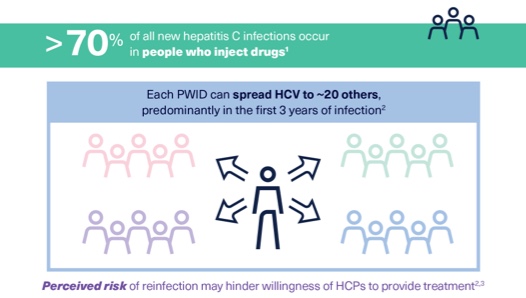

Mark understands the risk of contracting a disease or virus through shared needles, but is hesitant to approach a healthcare provider or visit an emergency room (ER) for testing. Previously, Mark was able to seek care from a mobile sexually transmitted infections (STI) testing center and was told he was positive for HCV. He was offered treatment and was cured after a few months, although he never sought follow-up care. Mark remembered the nurse telling him about the risk for reinfection of HCV, but he’s concerned about getting tested now because he’s uninsured and has been turned away in the past for that reason. One ER facility simply did not know how to screen and test him for Hepatitis C. Mark wishes it was easier for him to be tested and is looking for another mobile clinic, with little luck. He’s starting to experience some symptoms and is concerned he has contracted HCV again.

Persons experiencing homelessness are more likely to engage in behaviors, including injection drug use, which puts them at higher risk of HCV infection2

There are benefits to HCV treatment of PWID in a multidisciplinary care setting to reduce reinfection risk and address social and psychiatric comorbidities4

Explore how and why HCV reinfection occurs, including potential complications, how it is assessed, and treatment considerations.

1. Arum C, et al. 2021. Homelessness, unstable housing, and risk of HIV and hepatitis C virus acquisition among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet. 6(5):E09-E323. https://www.thelancet.com/article/S2468-2667(21)00013-X/fulltext.

2. CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/programresources/guidance/cluster-outbreak/cdc-hiv-hcv-pwid-guide.pdf. Last updated March 2018. Accessed November 22, 2021.

3. Marshall BD, Kerr T, Shoveller JA, et al. Homelessness and unstable housing associated with an increased risk of HIV and STI transmission among street-involved youth. Health Place. 2009;15(3):753-60.

4. AASLD-IDSA. https://www.hcvguidelines.org/unique-populations/pwid. Last updated September 21, 2021. Accessed October 13, 2021.